The Huns were a group of Eurasian nomads, appearing from east of the Volga, who migrated into Europe by the year 370 and built up an enormous empire there. Their main military techniques were mounted archery and javelin throwing. They were possibly the descendants of the Xiongnu who had been northern neighbours of China three hundred years before and may be the first expansion of Turkic people across Eurasia.

The Huns were a group of Eurasian nomads, appearing from east of the Volga, who migrated into Europe by the year 370 and built up an enormous empire there. Their main military techniques were mounted archery and javelin throwing. They were possibly the descendants of the Xiongnu who had been northern neighbours of China three hundred years before and may be the first expansion of Turkic people across Eurasia.As a boy, Aëtius was at the service of the imperial court, enrolled in the military unit of the tribuni praetoriani partis militaris. Between 405 and 408 he was kept as hostage at the court of Alaric I, king of the Visigoths. In 408 Alaric asked to keep Aëtius as a hostage, but was refused, as Aëtius was sent to the court of Rugila, king of the Huns. Aëtius's upbringing amongst militaristic peoples gave him a martial vigour not common in Roman generals of the time.

In 423 the Western Emperor Honorius died. The most influential man in the West, Castinus, chose as his successor Joannes, a high-ranking officer. Joannes was not part of the Theodosian dynasty and he did not receive the recognition of the eastern court. The Eastern Emperor Theodosius II organized a military expedition westward, led by Ardaburius and his son Aspar, to put his cousin, the young Valentinian III (who was a nephew of Honorius), on the western throne. Aëtius entered the service of the usurper as cura palatii and was sent by Joannes to ask the Huns for assistance. Joannes lacked a strong army and fortified himself in his capital, Ravenna, where he was killed in the summer of 425. Shortly afterwards, Aëtius returned to Italy with a large force of Huns to find that power in the west was now in the hands of Valentinian III and his mother Galla Placidia. After fighting against Aspar's army, Aëtius managed to compromise with Galla Placidia. He sent back his army of Huns and in return obtained the rank of comes et magister militum per Gallias, the commander in chief of the Roman army in Gaul.

The death of Rugila (also known as Rua or Ruga) in 434 left the sons of his brother Mundzuk, Attila and Bleda (Buda), in control of the united Hun tribes. At the time of two brothers' accession, the Hun tribes were bargaining with Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II's envoys for the return of several renegades (possibly Hunnic nobles who disagreed with the brothers' assumption of leadership) who had taken refuge within the Eastern Roman Empire.

The following year Attila and Bleda met with the imperial legation at Margus (present-day Požarevac, eastern Serbia) and, all seated on horseback in the Hunnic manner, negotiated a successful treaty. The Romans agreed to not only return the fugitives, but to also double their previous tribute of 350 Roman pounds (ca. 115 kg) of gold, to open their markets to Hunnish traders, and to pay a ransom of eight solidi for each Roman taken prisoner by the Huns. The Huns, satisfied with the treaty, decamped from the Roman Empire and returned to their home in the Hungarian Great Plain, perhaps to consolidate and strengthen their empire. Theodosius used this opportunity to strengthen the walls of Constantinople, building the city's first sea wall, and to build up his border defenses along the Danube. The Huns remained out of Roman sight for the next few years while they invaded the Sassanid Empire. When defeated in Armenia by the Sassanids, the Huns abandoned their invasion and turned their attentions back to Europe. In 440 they reappeared in force on the borders of the Roman Empire, attacking the merchants at the market on the north bank of the Danube that had been established by the treaty.

Crossing the Danube, they laid waste to the cities of Illyricum and forts on the river, including Viminacium, a city of Moesia (south bank of the Danube River). Their advance began at Margus, where they demanded that the Romans turn over a bishop who had retained property that Attila regarded as his. While the Romans discussed turning the Bishop over, he slipped away secretly to the Huns and betrayed the city to them.

While the Huns attacked city-states along the Danube, the Vandals led by Geiseric captured the Western Roman province of Africa and its capital of Carthage. Carthage was the richest province of the Western Empire and a main source of food for Rome. The Sassanid Shah Yazdegerd II invaded Armenia in 441.

The Romans stripped the Balkan area of forces needed to defeat the Vandals in Africa which left Attila and Bleda a clear path through Illyricum into the Balkans, which they invaded in 441. The Hunnish army sacked Margus and Viminacium, and then took Singidunum (modern Belgrade, capital of Serbia) and Sirmium (Pannonia, in northwest of Serbia). During 442, Theodosius recalled his troops from Sicily and ordered a large issue of new coins to finance operations against the Huns. Believing he could defeat the Huns, he refused the Hunnish kings' demands.

Attila responded with a campaign in 443. Striking along the Danube, the Huns, equipped with new military weapons like the battering rams and rolling siege towers, overran the military centres of Ratiara and successfully besieged Naissus (modern Niš, southern Serbia).

Advancing along the Nisava River, the Huns next took Serdica, Philippopolis, and Arcadiopolis. They encountered and destroyed a Roman army outside Constantinople but were stopped by the double walls of the Eastern capital. They defeated a second army near Callipolis (modern Gallipoli, a Hellespont-port).

Theodosius, stripped of his armed forces, admitted defeat, sending the Magister militum per Orientem Anatolius to negotiate peace terms. The terms were harsher than the previous treaty: the Emperor agreed to hand over 6,000 Roman pounds (ca. 2000 kg) of gold as punishment for having disobeyed the terms of the treaty during the invasion; the yearly tribute was tripled, rising to 2,100 Roman pounds (ca. 700 kg) in gold; and the ransom for each Roman prisoner rose to 12 solidi.

Their demands were met for a time, the Hun kings withdrew into the interior of their empire. Following the Huns' withdrawal from Byzantium (probably around 445), Bleda died. Attila then took the throne for himself, becoming the sole ruler of the Huns.

From 433 to 450, Aetius was the dominant personality in the Western Empire, obtaining the patrician rank (5 September 435) and playing the role of "protector" of Galla Placidia and Valentinian III while the Emperor was still young. At the same time he continued to devote attention to Gaul. In 436, the Burgundians of King Gunther were defeated and obliged to accept peace by Aetius, who, however, the following year sent the Huns to destroy them; 20,000 Burgundians were killed in a slaughter which probably became the basis of the Nibelungenlied, a German epic. That same 436 Aetius was probably in Armorica with Litorius to suppress a rebellion of the Bacaudae. Year 437 saw his second consulship and the wedding of Valentinian and Licinia Eudoxia in Constantinople; it is probable that Aetius attended at the ceremony that marked the beginning of the direct rule of the Emperor. The following two years were occupied by a campaign against the Suebi and by the war against the Visigoths; in 438 Aetius won a major battle (probably the battle of Mons Colubrarius), but in 439 the Visigoths defeated and killed his general Litorius and obtained a peace treaty. On his return to Italy, he was honoured by a statue erected by the Senate and the People of Rome by order of the Emperor; this was probably the occasion for the panegyric written by Merobaudes.

From 433 to 450, Aetius was the dominant personality in the Western Empire, obtaining the patrician rank (5 September 435) and playing the role of "protector" of Galla Placidia and Valentinian III while the Emperor was still young. At the same time he continued to devote attention to Gaul. In 436, the Burgundians of King Gunther were defeated and obliged to accept peace by Aetius, who, however, the following year sent the Huns to destroy them; 20,000 Burgundians were killed in a slaughter which probably became the basis of the Nibelungenlied, a German epic. That same 436 Aetius was probably in Armorica with Litorius to suppress a rebellion of the Bacaudae. Year 437 saw his second consulship and the wedding of Valentinian and Licinia Eudoxia in Constantinople; it is probable that Aetius attended at the ceremony that marked the beginning of the direct rule of the Emperor. The following two years were occupied by a campaign against the Suebi and by the war against the Visigoths; in 438 Aetius won a major battle (probably the battle of Mons Colubrarius), but in 439 the Visigoths defeated and killed his general Litorius and obtained a peace treaty. On his return to Italy, he was honoured by a statue erected by the Senate and the People of Rome by order of the Emperor; this was probably the occasion for the panegyric written by Merobaudes.In 443, Aëtius settled the remaining Burgundians in Savoy, south of Lake Geneva. His most pressing concern in the 440s was with problems in Gaul and Iberia, mainly with the Bagaudae. He settled Alans around Valence and Orléans to contain unrest around present-day Brittany (Peninsula on the north-west of France).

The Alans settled in Armorica caused problems in 447 or 448. It was probably in that period that he fought a battle near Tours, followed by a Frankish attack under Clodio to the region near Arras, in Belgica Secunda; the invaders were stopped by a battle around a river-crossing near Vicus Helena, where Aëtius directed the operations while his commander Majorian (later Emperor) fought with the cavalry. However, in 450 Aëtius had already returned in good terms with the Franks. In that year, in fact, the king of the Franks died, and the patricius supported his younger son's claim to the throne, adopting him as his own son and sending him from Rome, where he had been sent as ambassador, to the Frankish court with many presents.

In 447 Attila again rode south into the Eastern Roman Empire through Moesia. The Roman army under the Gothic magister militum Arnegisclus met him in the Battle of the Utus (on Vit river in Bulgaria) and was defeated, though not without inflicting heavy losses. The Huns were left unopposed and rampaged through the Balkans as far as Thermopylae.

Constantinople itself was saved by the Isaurian troops of the magister militum per Orientem Zeno and protected by the intervention of the prefect Constantinus, who organized the reconstruction of the walls that had been previously damaged by earthquakes, and, in some places, to construct a new line of fortification in front of the old. An account of this invasion survives:

-The barbarian nation of the Huns, which was in Thrace, became so great that more than a hundred cities were captured and Constantinople almost came into danger and most men fled from it. And there were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great numbers. (Callinicus, in his Life of Saint Hypatius)

In 450, Attila proclaimed his intent to attack the Visigoth kingdom of Toulouse by making an alliance with Emperor Valentinian III. He had previously been on good terms with the Western Roman Empire and its influential general Flavius Aetius. The troops Attila provided against the Goths and Bagaudae had helped earn him the largely honorary title of magister militum in the west. The gifts and diplomatic efforts of Geiseric, who opposed and feared the Visigoths, may also have influenced Attila's plans.

In 450, Attila proclaimed his intent to attack the Visigoth kingdom of Toulouse by making an alliance with Emperor Valentinian III. He had previously been on good terms with the Western Roman Empire and its influential general Flavius Aetius. The troops Attila provided against the Goths and Bagaudae had helped earn him the largely honorary title of magister militum in the west. The gifts and diplomatic efforts of Geiseric, who opposed and feared the Visigoths, may also have influenced Attila's plans.However, Valentinian's sister was Honoria, who, in order to escape her forced betrothal to a Roman senator, had sent the Hunnish king a plea for help – and her engagement ring – in the spring of 450. Though Honoria may not have intended a proposal of marriage, Attila chose to interpret her message as such. He accepted, asking for half of the western Empire as dowry.

| Belligerents | |

|---|---|

| Western Roman Empire (including many Germanic soldiers) Visigoths Franks Burgundians Saxons Alans | Hunnic Empire Ostrogoths Rugians Scirii Thuringians Bastarnae Alamanni Gepids Heruli |

| Commanders and leaders | |

| Flavius Aetius Theodoric † Merovech Gondioc Sangiban | Attila the Hun Valamir Ardaric Berik |

| Strength | |

| 50,000-80,000 | 50,000-80,000 |

Attila's army had reached Aurelianum by June. This fortified city guarded an important crossing over the Loire. According to Jordanes, the Alan king Sangiban, whose foederati realm included Aurelianum, had promised to open the city gates; this siege is confirmed by the account of the Vita S. Anianus and in the later account of Gregory of Tours, although Sangiban's name does not appear in their accounts. However, the inhabitants of Aurelianum shut their gates against the advancing invaders. Attila began to besiege the city, while he waited for Sangiban to deliver on his promise.

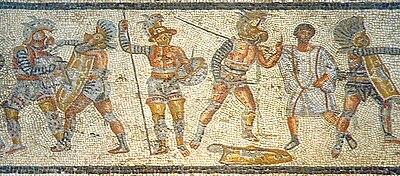

Now you are about to see the view that the generals wish to have, and see the Roman legions with barbarian soldiers of the roman foederati led by "the last of the true romans" against the strong and flexible hun cavalry and their supports led by the "Alexandre of Barbarians", the fight will decide the future of the romans empires and the peoples beyond the Roman-European borders, and the world will not to be the same before!